The phone rang. I can’t tell you the day. I can’t tell you the month. I can only tell you it was around 25 years ago, and the whispery voice on the other end of the line said: “Hi, it’s Burt Bacharach.”

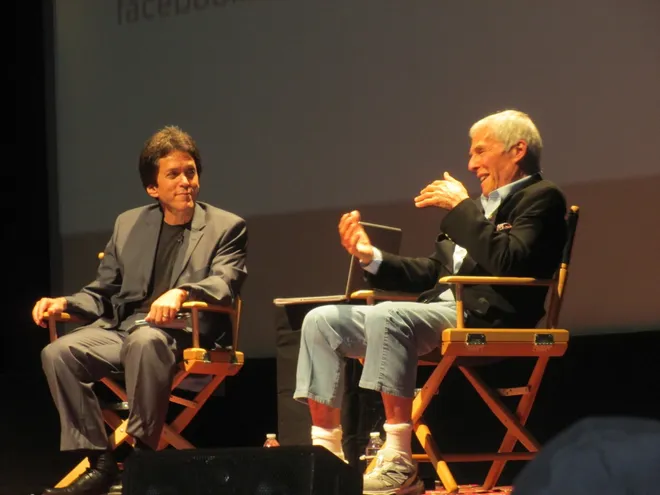

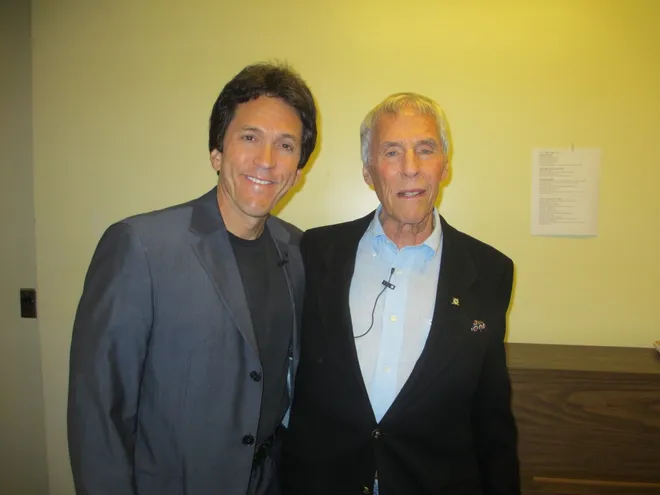

That started a most unlikely friendship. Burt had read one of my books (“My therapist turned me onto it,” he said, a line you don’t forget) and we met up in California and hit it off and we met again and did a few things together and later I wrote a novel about a musician that included him and he read his part for the audiobook, his rich, resonant narration telling an imagined encounter with my lead character.

But nothing I could have imagined compared to the real life — or the majesty — of Burt Bacharach and his music. He was gentle. He was elegant. He wore tuxedoes and had silver-flecked hair and even if you think you don’t know his work, you do, because there’s pretty much nobody over 20 in this country who hasn’t heard “Close to You,” or “That’s What Friends Are for,” or “What the World Needs Now is Love (Sweet Love),” or “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head.”

Burt wrote all of those, and hundreds more, many with the lyricist Hal David, and many with the lyricist Carole Bayer Sager, whom he also married. And while he’d be the first to tell you “I had a few stinkers,” most of what Burt wrote was, in a word, beautiful.

You can’t say that about all popular music. You can’t even say it about hits. Some hits are just catchy, or hooky, or uniquely recorded, but they don’t approach beauty.

Burt Bacharach didn’t just approach it.

He captured it.

He certainly ‘made everything great’

Listen to the song “Alfie,” a tune that Burt once told me, if he had to pick one thing he’d written to present at the gates of heaven, that would be it.

From the opening line, “What’s it all about, Alfie?”, you simply cannot imagine any other music marrying those words. The melody shifts, the tempo shifts, the whole swerve of the song shifts, several times, until it’s more like a story than a tune, but that’s what Burt and Hal David were aiming for.

I believe in love, Alfie

Without true love we just exist, Alfie

Until you find the love you’ve missed

You’re nothing, Alfie …

The result was that rarest thing: a complex musical composition that became a huge hit for multiple artists, including Dionne Warwick, Cilla Black, Stevie Wonder and Cher. Not too many songwriters could attract that mix of talent. But then, Burt wrote songs for so many artists, from the Drifters (“Please Stay”) to the Shirelles (“Baby It’s You”) to Jerry Butler (“Make it Easy on Yourself”) to Tom Jones (“What’s New Pussycat”).

He met his muse, Warwick, in a backup group he was recording, which included a young Cissy Houston, who brought her school age daughter, Whitney, to their sessions. Burt was a magnet for all kinds of talent. But he truly loved Warwick’s voice, it matched the versatility with which he liked to write (“The more we recorded, the more chances I could take” he said) and their partnership resulted in a laundry list of huge hits, from “Do you Know the Way to San Jose” to “Walk on By” to “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again.”

That last one is a perfect example of how brilliantly Bacharach would weave a melody so that, when it was over, you felt like you’d just listened to a catchy pop tune, yet he’d taken you through major, minor and diminished chord changes and even a key deviation.

“I never wanted to make it difficult for an audience,” he once told me. “I didn’t want to make it difficult to play …

“I just wanted to make everything great.”

Heartache followed him, too

Everything wasn’t always great for Burt personally. He couldn’t attend the best music schools because he’d been a “terrible student.” After serving in the Army, he was let go from an early gig orchestrating for Vic Damone because, he said, they claimed he spent too much time looking at women in the audience. He broke up his hugely profitable partnership with David over a petty business argument, a split he later regretted. (”You’re supposed to get smarter as you get older,” he lamented.)

He married often, four times total, once to actress Angie Dickinson after a drunken night in Las Vegas which culminated in a ceremony at 3:30 in the morning with Chuck Barris (of “The Gong Show”) as his best man.

“Why get married in such a fashion?” I once asked him.

“As opposed to what other fashion?” he said.

“Well, the kind where you set a date and invite people.”

“Oh, come on,” he said.

Burt’s first three marriages ended in divorce, and his daughter with Dickinson, Nikki, was born three months premature and died by suicide at age 40 in 2007 after a life battling autism.

So he knew tragedy, and heartbreak, as many great artists do. But he also knew joy, mostly when he was composing. He once said he had so much music running through his head, it was like “a jukebox” that woke him up at nights.

Who wouldn’t want to work with him?

The Beatles recorded one of Burt’s songs, so did Dusty Springfield and Christopher Cross (“Arthur’s Theme”) and Patti Labelle and Michael McDonald (“On My Own.”) He won Oscars and Grammys. He stamped careers. Aretha Franklin’s version of “I Say a Little Prayer” is still considered one of her classics.

Burt told me once he wished he’d written for Frank Sinatra, but apparently it wasn’t meant to be, During a stint in the early 1960s, when he was touring with the actress Marlene Dietrich, she told Sinatra he should record one of Burt’s songs but Ol’ Blue Eyes refused.

“You’re gonna be sorry,” Deitrich told him.

Years later, when Burt was famous, Sinatra called him out of the blue and said he wanted Burt to write a whole album for him, and Sinatra would record it. The only catch? They had to start the next day. Burt said he couldn’t, he was in the middle of the show “Promises, Promises.” A frustrated Sinatra, according to Burt, said, “Ah, forget it” and hung up.

So he didn’t work with everybody. Just pretty much everybody.

I remember visiting Burt once at a house he was renting in Del Mar, California. We sat on the beach as he watched his two young children play in the ocean. We ate lunch and talked about music and before I left, he asked me to write my phone number in his address book.

“Put it under the A’s,” he said, handing it over.

I squeezed it in between Herb Alpert and Charles Aznavour.

How’s that for a stable of friends?

Before I left that day, Burt handed me a CD of a yet-unreleased album he was doing with Elvis Costello. And as I put it in my bag, he quickly added, “The bass on Track 9 is still too high, so ignore that, and the drums on Track 11 are a little up, try and ignore that.”

Here was Burt Bacharach, the legend, still, like every musician I’ve ever known, tweaking the material even as he handed it over, trying to get it perfect.

I was speaking to a friend last week and said, “You know, I haven’t talked to Burt in a while. I’m going to call him.” And the next day, I read the headline, that Burt Bacharach had died of natural causes in his home in L.A. He was 94.

0 Comments