A fight to cure the incurable

Haitian child’s struggle with rare brain cancer inspires strangers, teaches doctors, and creates an unlikely family

She was born three days before Haiti’s massive earthquake in 2010. Her mother’s house collapsed around her. She slept that night on a bed of leaves in a sugar cane field.

But life would throw even bigger challenges at the brave and upbeat Medjerda (Chika) Jeune. Her mother died giving birth to a baby brother. Her family was scattered. Her godmother took her in, but gave her to an orphanage nine months later.

Then, two years ago this month, Chika’s mouth and eye drooped, and a Haitian neurologist, upon examining a brain scan, concluded, “Whatever this is, there is no one in Haiti who can help her.”

Free Press columnist Mitch Albom, who operates the Have Faith Haiti orphanage where young Chika lived, brought her to America thinking an operation and brief treatment would allow to her return to life among her fellow children.

But when U-M doctors diagnosed her with Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma (DIPG), a rare and always fatal brain tumor, the world shifted for Chika, Albom, and his wife, Janine. They became a medical combat unit, traveling the world in search of a cure for the incurable.

And in doing so, they became a family.

Albom chronicles their challenging, loving and ultimately heartbreaking two-year journey. It is an inspiring story of how a courageous little girl and two accidental parents — who didn’t look alike, talk alike, or come from the same world — created the most special of bonds in fighting the fight of their lives.

Chika's Story

How a little angel from Haiti — with an incurable brain tumor — captured hearts, changed lives and made a familyAPRIL 2017

We lay beside her in a single bed, my wife on her left, me on the right. We stare at her small chest, praying for it to rise. There’s one breath, we say — but then nothing for two seconds, five seconds, seven seconds — there, another breath. This is all wrong. She is young. We are old. Yet every minute her heartbeats slow, while ours are racing.

“Is she in pain?” I whisper.

“She is not in pain,” the nurses say.

A small plastic meter dangles from her middle finger, flashing digits, her pulse, her oxygen. For months, we have been fixated on this device, checking it nervously throughout the day and night. I hate it. I want to smash it into a million pieces.

Someone has figured how to put photos on the bedroom TV and they slide across silently, happy photos, Chika in a bathing suit, Chika writing on a blackboard, Chika with her face painted at a county fair, where she told the ride workers, “Guess where I am from?” “Haiti!”

Chika, 6, and Mitch Albom take a selfie at a Franklin playground in May 2016. They spent most of their time together. He taught her about America. She taught him about life.

The phone rings. No one answers. An oxygen machine thrums and sputters, breathing more regularly than she does. A plastic tube trails from her nose to her ears and behind a pink ribbon in her hair.

Pink. She loved pink.

Loves pink. She is still with us.

Breathe, I say silently.

She makes a small noise, like the squeal of a deflating balloon.

“Are you sure she’s not in pain?” we ask.

“She is not in pain.”

“Then why–’’

“In the final minutes, these are the sounds children sometimes make.”

These are the sounds children sometimes make.

It seems so clinical, like we are observing a copy machine, not a 7-year-old. I glance at my wife. Her eyes are dripping tears. I look at Chika, this little girl — not our girl, and yet, our girl. Our girl. In every way, our girl.

The phone rings. No one answers. Once, the sounds from her little mouth were joyous; squeals of delight at her first American hot dog, high-pitched laughter while descending her first sled hill, and singing — always singing — like an Ethel Merman in size 1 shoes, belting out Creole prayers in our suburban Detroit home the way she once did at a Port-au-Prince orphanage, seeking the Lord’s ear beneath starry Caribbean skies.

That was before the long journey here, the operations, the catheters in her head, our worldwide search to cure the incurable, and the endless decisions we were forced to make — Which doctor? Which drug? Which country? — all funneled into this, here, now, a warm Friday afternoon, and one last choice:

How to watch her die.

Chika, someone asks, what do you want to be when you grow up?

“Big,” she says.

We have chosen to surround her in bed, the way she always loved. We rub her narrow shoulders. We run fingers over her soft cheeks. We look again at the gentle face that rests between us, her large eyes mostly closed now, like someone fighting sleep.

It is a face that touched the lives of so many.

A face that changed the doctors’ thinking.

A face that brought parenthood to a man and a woman too old to be parents.

“It’s all right, Chika,” we whisper. “We’re right here, Chika …”

The phone rings. No one answers.

MAY 2015

The phone rings.

“Hello, Sir?”

Yes, Alain?

“Something is wrong with Chika.”

This is how it begins. Alain Charles, the 32-year-old director at the Have Faith Haiti Orphanage/Mission in Port-au-Prince, has a habit of delivering news in declarative statements. “We have no water.” “The van is broken.” “There’s something wrong with Chika.” It is up to me, as the person operating the orphanage, to explore the particulars.

What’s wrong with Chika, Alain?

“Her face is funny.”

How is it funny?

“It is lowered. Her mouth. And her eye.”

Lowered? You mean drooped?

“Drooped. Yes.”

Did you take her to the doctor?

“Yes.”

What did he do?

“He gave her eye drops.”

Alain, it’s not her eyes. It might be something they call Bell’s palsy.

“Yes, sir.”

Do you know what that is?”

“No, sir.”

She needs a neurologist.

“Yes, sir.”

Can you find one?

“I think so.”

We need to find one.

“Yes, sir.”

* * *

What followed seems monumental compared to that simple conversation, but then, simple things often turn monumental in Haiti, the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. Daily life is a hot, exhausting struggle. Money is scarce. Water is scarce. Food is scarce. And children die.

Often.

Seven out of every 100 Haitian children will pass away before their fifth birthday — 10 times the rate of the U.S. The fortunate families get some kind of explanation. The others, who lack money, live in far-off provinces or can’t reach a doctor, get nothing. “Ca se volonte Bondye,” they lament, This is what God wants — although, in most cases, death may be less about God than malnutrition, injury, childbirth complications or pneumonia.

But even by Haitian standards, what struck 5-year-old Medjerda (Chika) Jeune was crushing.

And rare.

A proud, curious child with full cheeks, pouty lips and eyes as big as Haitian mountains, Chika had never exhibited health problems before. She was fond of pushing around the boys at the orphanage, or diving into a second helping of rice and beans, or dancing wildly during church services to the beat of conga-driven devotions.

Chika, 5, gets an MRI. Doctors called her ability to lie still and endure the procedures “remarkable.”

But in late May 2015, she sat next to Alain, with her drooping mouth and droop- ing eye, inside a dimly lit Port-au-Prince medical facility, awaiting the sole MRI ma- chine in their country.

Alain had followed protocol: show up early and pay cash in advance (750 U.S. dollars). Haiti has no private medical insurance to speak of. More than 75% of health care costs come out of people’s pockets.

Finally, after several hours, a nurse emerged and told Chika to drink some syrup. It made her sleepy. She was carried through a door and placed inside the machine. Halfway through the process, Chika woke up, asking where she was. More syrup was given. Again, she fell asleep. The MRI finished, and Alain and Chika went home.

When the results were in, Alain was given the scan and a note. No explanation. He took them to a neurologist.

“It is something in her brain,” the doctor said. “It is very bad.”

“What should I do?” Alain asked.

“Is there any way you can get her to the United States?”

“Why?’’

“Because whatever this is, there is no one in Haiti who can help her.”

JANUARY 2010

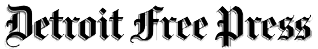

Chika is baptized in 2010 as Haiti is recovering from its worst earthquake in nearly 200 years.

She is born on Jan. 9, three days before the worst earthquake to hit her country in nearly 200 years. She comes so quickly, her mother doesn’t have time to call the midwife, an older man named Albert. By the time he gets to the house, the baby is already in the world.

They formally name her “Medjerda,” a made-up name, but she will soon answer to “Chika,” a made-up nickname. Her mother, Rezulia Guerrier, is a tall, strong woman in her mid-30s who sells small items in the street for money. Her father, Fedner Jeune (the parents are not married), has experience with construction but, like many men in Haiti, looks for work and rarely finds it. He is around and not around.

On the third day of her life, Chika lies in bed with Rezulia in their one-room cinder-block house, taking shelter from the afternoon heat. At 4:53 p.m., the ground starts shaking as if thunder were just outside the door. In seconds, the house splits in two and crumbles around them, leaving mother and child exposed like a cracked-open walnut.

It is a 7.0 magnitude earthquake with an epicenter less than 16 miles from Port-au-Prince, the capital city. Nearly 3% of Haiti’s population will die from it. Ten percent — almost a million people — will be left homeless, including Rezulia, Chika and her two older sisters.

They spend that night in the sugar cane fields. Chika’s bed is a layer of leaves. The country is in ruins.

The baby sleeps.

JUNE 2015

It was not easy to get Chika into the U.S. Even with help from Michigan Sen. Debbie Stabenow, who had once visited our orphanage, it took several weeks of phone calls and filings. Getting a passport. Medical affidavits. Securing an interview at the U.S. embassy. (No one moves fast in Haiti, even for terminal illness.)

Chika finally cleared her paperwork, and on June 3, holding Alain’s hand, she boarded her first airplane, at the same hour her friends at the orphanage were lining up for school. She arrived in Detroit late that night, wearing a pink dress and a white sweater and shivering from the air conditioning. In a bathroom, she turned a sink handle and yelled, “Oooh!”

She had never experienced hot water from a faucet.

In her time at the orphanage, Chika had always been curious. But this trip would test her sense of wonder. Every moment was a discovery. Every item was worth touching. We took her to Mott Children’s Hospital in Ann Arbor where they gave her a sticker (“Look!” she cooed) and she posed with a Superman statue. When the elevator lifted — her first ride — she beamed as if watching a magic trick.

That afternoon, she lay inside another MRI machine. The results left doctors skeptical. It was a brain tumor, a significant one, the kind often deemed not worth the risk of surgery. Days passed. They deliberated. Eventually, at a tumor board meeting, the members voted, by a narrow margin, to proceed with an operation, in hopes that, despite its size, what had invaded this little girl’s head was still a lower grade glioma.

On June 15, less than two weeks into her first trip out of Haiti — and not yet 4 feet tall — Chika was given a light blue gown, some yellow socks and an intravenous needle drip in the back of her hand. She was rolled away to surgery and my wife, Janine, and I were handed a pager.

“Wait until it vibrates,” they told us. We waited.

DECEMBER 2010

Baby Chika is baptized. Her cinder-block house is rebuilt. As Haiti struggles to recover from the earthquake, Chika learns to walk and talk. She sleeps beside her mother atop a single mattress on the dirt floor, along with her two older sisters.

They eat once a day. There is no electricity and no indoor plumbing. Chika is bathed in a bucket, with a can of water poured over her head. The water comes from a well on another property.

Sometimes, when Rezulia goes to a muddy river to wash clothes, she takes Chika with her. Years later, Chika will claim to remember those journeys. She will tell strangers in America, “My mommy used to take me to the swimming pool.”

“Degaje pa peche” says a Haitian proverb. To get by is not a sin.

JUNE 2015

Chika, 5, after surgery at Mott Children’s Hospital in June 2015. Dr. Hugh Garton found malignant tissue wrapped throughout healthy tissue.

In the operating room at Mott Hospital, the neurosurgeon, Dr. Hugh Garton, found himself dealing with a monster. The tumor tissue in Chika’s brain was everywhere, wrapped throughout the healthy tissue. He could remove only 10% before disturbing vital elements of the brain itself.

What he did remove was sent for pathology analysis.

“Let’s hope for the best,” he said.

He forced a smile. There remained a slim belief that, despite the cancer’s spread, it was just Stage I, or at worst, Stage II.

Were that the case, with treatment, Chika could eventually return to the other kids in Haiti.

And we would return to our previous life.

Which was what I always thought would happen.

And.

It was never going to happen.

AUGUST 2012

Chika’s mother dies.

It happens as she is giving birth to a son, inside the cinder-block house. The midwife — Albert, the same man who arrived late for Chika’s birth — does not realize how much blood Rezulia is losing. The boy is born with her last breath. He enters the world as a motherless child.

No one is called. No police. No investigation. Rezulia is buried the next day, in a nearby field.

Chika never gets to say good-bye.

The children are scattered among relatives, the stunned father unable or uninterested in caring for them. The newborn son goes to an uncle. The sisters are split up.

Chika is taken away by her godmother, a friend of Rezulia’s named Herzulia Desamour. “From now on, you will live with me,” she tells Chika. They share a one-room apartment by a church, with Herzulia’s husband and their three other children.

Chika eats mostly rice. Her mattress is in a corner. She tends to her own soiled sheets, carrying them up steps to dry on the roof, even though she is barely 3 years old.

In the spring of 2013, less than a year after taking her in, Herzulia puts Chika in a dress and loads her inside a Haitian “tap tap,” a rickety share taxi with a back door open to the traffic exhaust. Her destination is the Have Faith Haiti orphanage/mission, which I have been operating since 2010.

She wants us to take the child.

I do the admission interview. I hear Herzulia say there is no money for this extra mouth to feed, that her own family can barely get by.

I wave at the full-cheeked girl in front of me. She waves back. I make a face. She makes one back. A good sign, I think. Most Haitian children keep their heads down during these interviews.

I tell Herzulia we will consider her request. She leaves holding Chika’s hand. Neither one looks back. But later I learn that every day that followed, Chika asked, ‘Kile blanc ap voye chache’m?”

“When is the white man going to send for me?”

* * *

Chika, 5, who was homeschooled, practices her spelling in the Albom family home, just after her first brain surgery in the summer of 2015.

I should say something here about my background. Although I have operated the orphanage/mission in Haiti since 2010, and make monthly visits to our 39 children there, my wife and I have no kids of our own. We were married in our late 30s, and despite our efforts, parenthood never happened. In time, we gave up trying, and a layer of acceptance settled in like sea fog, blocking the particular light of children from ever reaching us.

Our brothers and sisters almost all had kids, and there were a lot of them: 15 nieces and nephews. We celebrated their milestones — birthdays, communions, graduations — we gave cards and kisses and presents that were too big, and in the car rides home we spoke about how cute they were, how big they were getting, but we never spoke about any emptiness we were feeling. We made our lives busy. We traveled. Our house was spacious and mature, lacking stray toys or crayon drawings on the refrigerator. We fell into that category that is both envied and pitied: The Couple Without Kids.

So it may seem strange that, in our late 50s, we found ourselves in a meeting room at Mott Hospital, looking every bit like a mother and father, side by side, braced for the news, parental in our posture, our furrowed brows — parental in everything except an actual relationship to the child.

But there we were. And with the biopsy results in, Dr. Garton, a thin, fit man who enjoys mountain climbing, had to scale a less pleasurable rock; telling the de facto parents about Chika’s disease, and adding a new four-letter word to our vocabulary: DIPG.

It stands for Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma, an insidious cancer of the brain stem that is nearly exclusive to children. It is the worst kind of tumor: the kind for which they don’t bother giving you hope.

DIPG is aggressive and debilitating, invading the pons, which controls most of the body’s vital functions (heart rate, swallowing, breathing). It is rare — only 300 kids in the U.S. are diagnosed with it each year (there are no statistics for Haiti). And yet, because of its severity, it is the leading cause of death from pediatric brain tumors.

What is DIPG?

DIPG—Diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas—are highly aggressive and difficult to treat brain tumors found at the base of the brain. Children are typically diagnosed between the ages of 5-7, and the average survival rate is 9 months from diagnosis. DIPG is difficult to treat because of its location—the pons, a very small area of the brain stem responsible for key body functions such as breathing, swallowing, and eye movement—and because it is diffuse (not a single mass but spread out and mixed with healthy cells). A rare form of cancer, research for it is underfunded.

This is the bad news. Then comes the worst news: In more than 50 years of study, since astronaut Neil Armstrong’s 2-year-old daughter died from it in 1962, no real progress has been made.

Survival rate is, essentially, zero.

“The average life expectancy without treatment,” Garton explained, “is maybe five months. If Chika gets radiation you could extend that another five or six months. But …”

But?

“There’s a price to pay for radiation. It goes on for weeks. It’s not fun. Kids don’t like it. And there are potential complications. She’d be on steroids. She could get tired, vomit.”

He looked at us empathetically. He knew about Haiti. He knew about the 38 children Chika called her family. He knew how far Ann Arbor was from Port-au-Prince.

He knew how old we were.

“Maybe,” he said, softly, “it would be better if you took her back, and let her live out her final months there.”

I looked at Janine. She looked at me. The Couple Without Kids now faced a decision no couple with kids should have to face: to put a child through a hopeless medical marathon, or to stoically accept a doomed fate.

We went back to the room where Chika was recovering. Her head had been bandaged up high, like a white fez. Someone had brought her breakfast, and when we entered, Chika was in a chair, working her way through a blueberry muffin. All our kids in Haiti love to eat, having been hungry much of their lives. But here was this round-faced little girl, her skull only recently cut open, ignoring all distractions, focused intently on digging a fork into a muffin and trying to get it to her mouth before it crumbled.

And I knew what our answer would be. She was a fighter.

So we would be fighters.

“If she goes through the radiation, she has to be here for months,” the doctor had said. “Does she have someone to stay with?”

Without even looking at one another, Janine and I said, “Us.”

And that is how a family was born.

JULY 2015

Here is Chika rolling on the carpet of my office, playing with flash cards. She has been here five weeks, and I am working on her English.

“Five plus ONE!” she yells. How much is that?

“SIX!”

Check the back, I say.

She checks it.

“I was … white!”

You were right.

“I was … wwwwrrrright!”

She giggles wildly. I point to a chair. Where is the chair? I ask.

“There is it!”

There it is, I say. Not “there is it.”

“There … it … is.”

Where is the paper?

“There is it!”

There it is, I say.

She stops, squints and looks at me. “Where is the odder kids?” she asks.

I realize she means the children at the mission. Is she missing them? Missing her home? I point to a photo of them on my desk.

“There is it!” she yells.

* * *

We got a second bed.

This would be where Chika slept — at the foot of our own bed and a few feet from the armoire. Janine and I had to quickly reset the house. We’d owned it for 24 years; it was organized, down to the throw pillows on the couch.

But your world turns elastic when a child arrives. And so our kitchen cabinet was stocked with Cheerios, and little shoes appeared in the closet, and a hanging rack of pint-sized clothes took root in our bathroom. Everyone who came by seemed to bring a toy, and we quickly collected a basket full of stuffed ponies, talking dinosaurs and silky-haired princesses.

Chika’s new bed was made up with a colorful blanket from Disney’s “Frozen.” The first night she slept there, we kissed her, got under our covers, and heard her little voice from somewhere below our feet:

“Goodnight, Mr. Mitch. Goodnight, Miss Janine.”

To be honest, nothing was the same after that.

* * *

Cancer is speed. Broken down, that’s where it draws its power. The malignant cells spread illogically fast, splitting and multiplying and defying efforts to slow them.

As those cells were racing through her healthy brain tissue, Chika was racing through a brand new world. She’d rumble around the living room in a circle, touching each piece of furniture. She’d stand by a large window and scream, “Bird!” Everything was a revelation. The TV set. The dishwasher. When we drove her to the hospital, I watched her wide-eyed gazing out the car window, billboards, fast food outlets, a passing limousine. What must she be thinking, I wondered? Her sensory input was on overdrive.

Perhaps that’s why she loved to hide. When I came in from the outside, she would pull a blanket over her head and yell, “Mr. Mitch? Where is Chika?”

“Hmm, where is Chika?” I’d repeat. I’d fake a search. When I finally unearthed her, she’d howl with laughter.

“There is she!” she’d yell.

“There she is,” I’d correct.

Her radiation began. Five days a week for six straight weeks, on a lower level at Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak. She was fitted for a helmet and had to lie on a slab, as a giant machine shot a beam at her tumor in hopes of destroying DNA in the cancer cells while leaving healthy cells intact.

Chika understood none of this. Only that she had to stay still — and if she was good, we would go for ice cream or to the toy store. We had chosen not to explain cancer to her. We didn’t nickname her tumor. We told her only that she was a little sick right now, and these treatments would make her better. Our thinking was, she’s a child, let her be a child. There’s no right way to do it. You pick a path. This was ours.

“How old is she again?” the radiation oncologist, Dr. Peter Chen, asked one morning as we watched from a monitor outside the room.

“She’s 5,” I said.

“Really?”

“Why?”

“She’s lying so still. She’s better than the adults we treat.”

“Well, she’s 5,” I said.

“Remarkable,” he mumbled.

* * *

I observe how quickly her English improves. She, meanwhile, is observing me.

One day, at the table, I am reading a com- plicated contract.

Oh, boy, I sigh.

“Why do you say ‘oh, boy’?” she asks. “There is no boy here.”

It’s just something people say when they are tired, I say.

She thinks.

“Why don’t you say, ‘Oh, girl?’

She loves to sing but the words are her own. Mary had a little lamb — “whose crease was crise of snow.” A spoon — “from the sugar” — makes the medicine go down. When I correct her, she insists, “It’s my mouth, I can say it the way I want.”

One morning, she makes an observation.

“Mr. Mitch, when you sleep, you sound like a bear.”

Janine laughs. I laugh. Chika laughs at us laughing. She makes a snorting sound and we laugh even harder. She is so happy, so pleased. There is rare delight, I recall, in making your parents crack up.

Even if we are not her parents.

AUGUST 2015

Radiating a brain tumor can cause swell- ing, or edema. So steroids are prescribed to reduce that risk, which in turn quickly puff up a child. This is why, in photos of DIPG kids, they often seem ill-formed, their faces grotesquely swollen.

In Chika’s case, the doctors prescribed Dexamethasone (a substance, I noted, that will get you thrown out of the Olympics). I had written about steroids over the years, decrying their risk and long-term consequences. I silently cringed when she swallowed them every morning, hidden inside a spoonful of applesauce.

Breakfast had become part of our routine, scrambled eggs, toast and, as the steroids increased her appetite, more eggs, more toast — plus avocado, tomato, jelly, cereal. Chika insisted that she could make the eggs (after watching me do it) so I stood behind her as she scrambled them in a bowl. She came up to my waist and sometimes I would wiggle my fingers in her hair.

“Hey,” she would say, laughing, “stop doing that!’’

“But I like it,” I’d say.

“Ohhh-k,” she’d relent.

One day, as I did this, her hair came out in my fingers. She turned and looked. I quickly closed my fist.

Soon, such changes were obvious. Chika’s soft, round face grew large and distorted (the steroids). Her middle swelled. Her thighs puffed. She ballooned from 48 pounds to 72 pounds. Lifting her became a challenge.

More patches of hair fell out. At night, her head got hot and she sweated, and at times she would scream during her sleep, much of it in Creole that we did not understand. In the morning, we asked if she had a bad dream, and she sometimes said, “I dreamed about a monster.”

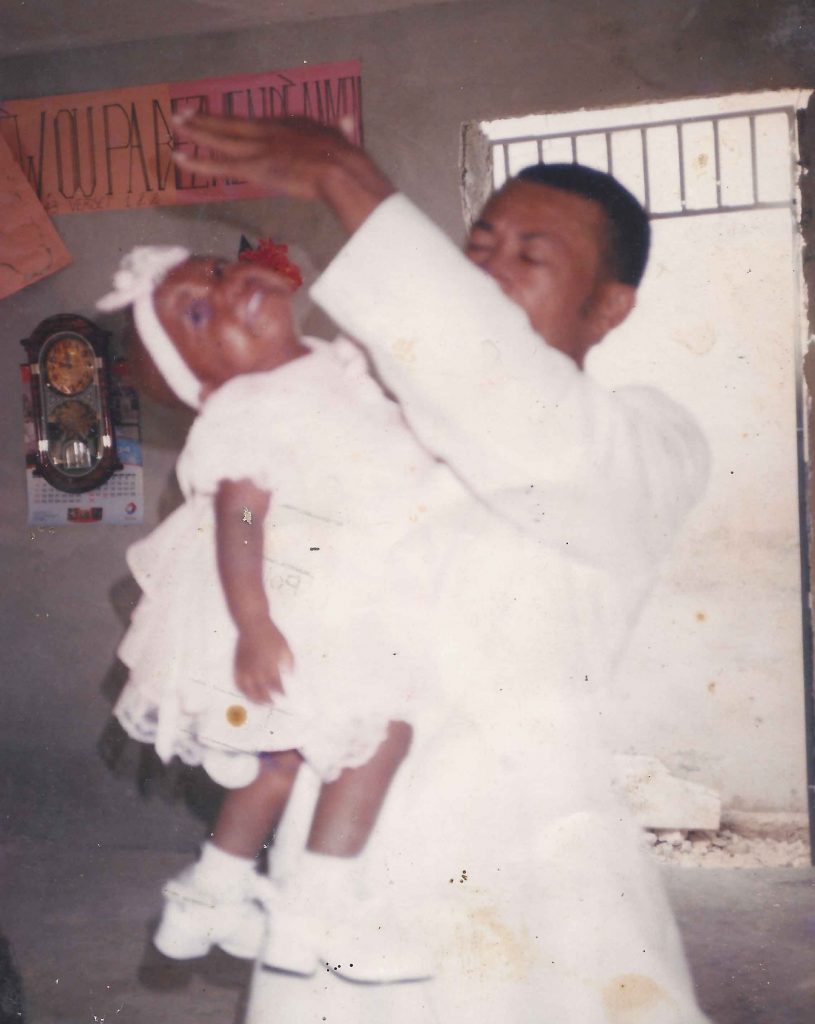

Chika and Mitch Albom during their morning and evening teeth brushing at the Alboms’ home in July 2015. They bonded during the daily task.

We went through the summer this way, shuffling her to medical appointments, doctors, homeschooling her at the house. I fell behind on jobs. I was late filing stories. The parenting process hijacked every hour we used to have for ourselves.

And yet, it never felt like a burden. More like a new purpose we had suddenly tumbled into, rendering our old life a phone call that we just couldn’t make, or an appointment we just kept missing.

Janine and I divvied up the daily tasks of keeping Chika occupied, Janine taking the dressing, the showering, the tea parties and game playing, while I handled the doctor appointments, the food gathering, the toy store runs — and the dental care.

Each morning when Chika rose and each night before she went to bed, I would squeeze toothpaste on her newly purchased toothbrush. She’d developed some gum issues, so I added mouthwash in a little cup. As she went through her routine, I stood behind her, studying our reflections in the bathroom mirror, and the obvious contrasts in our ethnicity.

I wondered how Chika saw us. Black? White? Haitian? American? She never asked about our differences, although in that mirror we could not have looked more opposite, short, tall, dark-skinned, light-skinned. It didn’t matter. We were there to brush teeth. Eventually, I would say, “OK, spit” and she would do so and laugh.

One night, Chika clomped ahead of me to the bathroom. She shut the door mischievously, before I could get in.

“What are you doing, Chika?”

“Just a minute!” she yelled.

Just a minute?

I knocked again.

“Just a minute!”

Finally, when she hollered, “OK!” I entered saying, “Chika, come on, you can’t shut—“

I stopped. She had laid two toothbrushes side by side, squeezed out the toothpaste, and lined up two cups of mouthwash.

“Now, you can brush your teeth with me,” she said.

As the doctor said. Remarkable.

* * *

On a monthly visit to Haiti, one of our young boys asks me, “When is Chika coming back?”

He asks in front of a dozen other kids standing in the dusty yard. I have been avoiding this question. I don’t want to lie. I tell them Chika is getting treatment from the doctors and we hope to bring her back for a visit soon.

“Does she sleep with you and Miss Janine?”

Yes.

“In your bed?”

She has her own.

“Does she eat with you?”

Yes.

“Beans and rice?”

Other things.

“Does she have dolls?” Some dolls.

“Which ones?”

I don’t know their names.

“Should we pray for Chika?”

Always.

“Every night?”

Every night.

They look off, as if trying to comprehend all this. It is hot, as usual, and they squint in the sun. One girl raises her hand.

“When Chika comes back, can she bring the dolls?”

SEPTEMBER 2015

Anyone dealing with a terminal illness today will, at some point, face a fundamental decision: explore the Internet, or not.

We avoided it for months, having once scrolled the “DIPG” entries and seen countless heartbreaking Facebook posts and wide-reaching but often contradictory suggestions. It seemed confusing, even depressing, photographs of swollen children, holding teddy bears at fundraisers, making final trips to Disneyland, parents bravely pushing up smiles. And the medical conclusions were all over the map. Try this. Don’t try this. This worked. This didn’t work.

I stopped looking. Wanting to believe our case was unique, however naive that was, held off a crashing wave of hopelessness.

So instead of the Internet, I spoke with doctors, I called them, hounded them — especially the pediatric oncologists at Mott, Dr. Pat Robertson and Dr. Carl Koschmann. I asked them constantly about alternative treatments. What were other researchers finding? What were the latest drugs? What about Europe? I’d been warned that radiation provides a “false honeymoon” for DIPG kids, and could improve Chika to a point where we thought she was OK.

“Don’t be fooled,” they cautioned, “the tumor comes back — and stronger.” So I tried to be preemptive. Unfortunately, besides radiation, there is no real treatment for DIPG. What exists are clinical trials, experimental drugs, a potpourri of unproven choices, like some massive medical casino. Choose your odds. Place your bets.

Meanwhile, during this time, DIPG was unusually present in our local news.

Chad Carr, the 4-year-old grandson of Lloyd Carr, the former Michigan football coach, had been diagnosed with the disease, in the fall of 2014. His parents, Tammi and Jason Carr, had made his battle public, to raise awareness of the disease. Stories were written. Photos were taken. Events were held. A hashtag — #ChadTough — was created.

On the afternoon of Sept. 12, 2015, I was at Michigan Stadium, covering the Wolverines football game against Oregon State. Just before kickoff, the crowd rose and cheered.

Chad Carr was being carried onto the field by his family.

The stadium announcer bellowed, “Joining the game captains for the coin toss is Chad Carr. Our thoughts and prayers are with the Carr family…”

At that moment, more than 100,000 spectators knew this little boy was fighting for his life. It might have been natural to tell a colleague, “I have a child with that same cancer.”

I didn’t. I kept quiet. I went home and never mentioned it to Janine. I knew, deep down, this was folly, thinking silence could affect anything. But when it comes to facing a child’s certain death, folly is underrated.

OCTOBER 2015

We are in New York City. We have committed Chika to an experimental procedure run out of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, something called CED, Convection Enhanced Delivery. In this process, a catheter is inserted directly into the tumor, and a radioactive iodine, attached to an antibody, is dripped through the tube and into the cancerous tissue. The theory is this will be more effective, because CED circumvents the blood-brain barrier that keeps other drugs — even chemotherapy — from ever reaching the trouble spot.

It is the second time in four months that doctors will break through Chika’s skull.

Chika had an experimental procedure at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York in October 2015. Steroids to reduce brain swelling caused her to have a puffy appearance.

We try to make the trip an adventure. Chika has never been to a city like New York, and her head is a swivel. Her new word is “Hey!” and she puts it before everything.

“Hey! That building is so tall!”

“Hey! There is a horse in the street!”

I think about what she is about to go through. I hug her close and put my head on top of hers.

“Hey! Why do you lean on me? I am not a bed!”

She is giddy with the energy of Manhattan, and Janine and I each take a hand as we lead her across busy intersections. I realize, had things been different, this could be a snapshot of us 30 years earlier, a happy young family darting across the street.

Now we look like grandparents.

We visit Serendipity on the East Side, a restaurant famous for gargantuan frozen hot chocolates. We get Chika one and take photos of her sipping it. Bloated by the steroids, her face and belly are huge, and I notice an older woman looking at her with an expression that says, “Does she really need to eat more?” I glare back.

Later, we walk Chika through Times Square. There are people dressed as Superman, Spiderman, Olaf. We take photos. One of the characters, on a break, removes his large cartoon head.

“Hey!” Chika screams. “There is a man inside Mickey Mouse!”

That night, in the hotel room, we sit with Chika between us on the bed. I rub her cheeks. She has been taking liothyronine and super-saturated potassium iodine to block the potential harm to her thyroid. We have been warned that this operation, which requires precise, hours-long, computer-aided placement of the catheter, might be dangerous. I’ve been given a form that lists the possible risks:

■ Coma.

■ Potentially uncontrollable seizures.

■ Death.

I ask myself who am I to sign this? What right do I have? Who gave me that power?

And then I remember checking in at the hospital and being given a badge that read “PARENT.” And I sign the form, because as a parent, even a substitute one, letting Chika sink is not an option. I put on a happy face and hide behind it as I play with her, like a man inside a Mickey Mouse.

NOVEMBER 2015

Chika meets Michigan football coach Jim Harbaugh in a Cracker Barrel store in November 2015. Not knowing anything about her, he was moved by her joyous spirit and bought her a toy guitar.

Chika made it through the procedure. In truth, she sailed through it, which gave us hope. The lead doctor, Mark Souweidane, a pediatric neurosurgeon, was pleased with the way the treatment spread around the tumor. He showed us a scan, the luminescent green being the radioactive agent; it was like watching Kryptonite invade Superman’s head

I realized how many times I had now seen Chika’s brain on film. When previous scans were put side by side, it was clear that something we had tried had shrunk the tumor by a significant degree.

“This is good, right?” I’d ask the doctors.

“It’s good,” they’d say, but there was always something behind their response, a hesitation, a filter; I was stung that they would not share my enthusiasm. Had they become that hardened to good news?

Chika, for her part, remained nonplussed, asking mostly about toy stores or a trip back to Haiti. No matter where we dragged her, or how much weight she gained, we were astonished at her lack of a complaint gene. The closest she came was after her surgery at Sloan Kettering, when Janine took her into bathroom, and she looked in the mirror, and realized the doctors, in clearing a path for the catheter, had shaved a 3-inch square patch of her hair just above the forehead. It looked as if someone let a lawnmower run over it.

“Hey!” she declared. “What happened to my hair?”

We bought her headbands with big flowers to cover the spot.

She was happy once again.

CHRISTMAS 2015

For the first time since leaving for treatment, Chika returned to Haiti in December 2015. Her arrival was triumphant. The kids painted a welcome mural and when the SUV pulled up, chanted “Chi-ka! Chi-ka!”

Keeping a promise, I take her back to Haiti. She bounces up and down as the airplane lands. If not for the seat belt, she might fly away.

In the Port-au-Prince terminal, a five-piece band plays just beyond passport control, and Chika stops to dance freely in front of them, a smile pasted across her still-chubby face.

Her arrival at the orphanage is triumphant. She hides behind the seat when the SUV pulls in, but she can hear chants of “Chika! Chika!”

The other kids mob the door, calling her name.

Amid an ocean of wild hugging and squeals from the happy nannies, she strips off her sweatshirt and runs to the swing set. The other kids surround her, pushing her higher. As she rises into the Haitian air, her face is a portrait of relief.

She is home.

That night, she returns to her lower bunk bed in a crowded room of 13 other girls. In Michigan, she has accumulated a bevy of dolls, shelves of books, games and toys.

Here, she has none of that. Just a cubby for her clothes and a toothbrush in the common outdoor sink area. But if she misses anything, she does not show it. She falls in line for meals, for showers. I wait for her to hold court, regaling the other kids with stories of her U.S. adventures. It never happens. Perhaps talking about America reminds her she will have to go back.

I give small toys to all the kids. After a day, Chika’s breaks. She brings it to me to fix.

I get a screwdriver. I fix it. Chika says “thank you” and runs off happy.

Kids expect grown-ups to fix things. I know, deep down, she expects us to fix her.

We’re trying, Chika. We’re trying.

Chika, right, and her friends from the Have Faith Haiti Orphanage in December 2015. She was excited to see them after returning from Michigan. In Haiti, she was back in her bunk in a crowded room of 13 other girls.

FEBRUARY 2016

If terminal cancer allows a “honeymoon” period, we were surely in it during the early months of 2016. Chika’s walking had improved greatly. She could swim (something she loved). Her left eye had readjusted, her smile was nearly even, and her body was slowly returning to normal, the steroids, blessedly, no longer needed.

On a visit to Mott, Chika took off down the hallway, then ran back and jumped, unexpectedly, into Dr. Robertson’s arms. “Oooh,” the doctor said, nearly knocked backward. She hugged Chika, and I silently took pride in how well this little girl — our little girl — was performing.

“She’s doing great, right?” I said.

“Uh-huh,” came the reply, again, in my mind, less enthusiastic than I wanted.

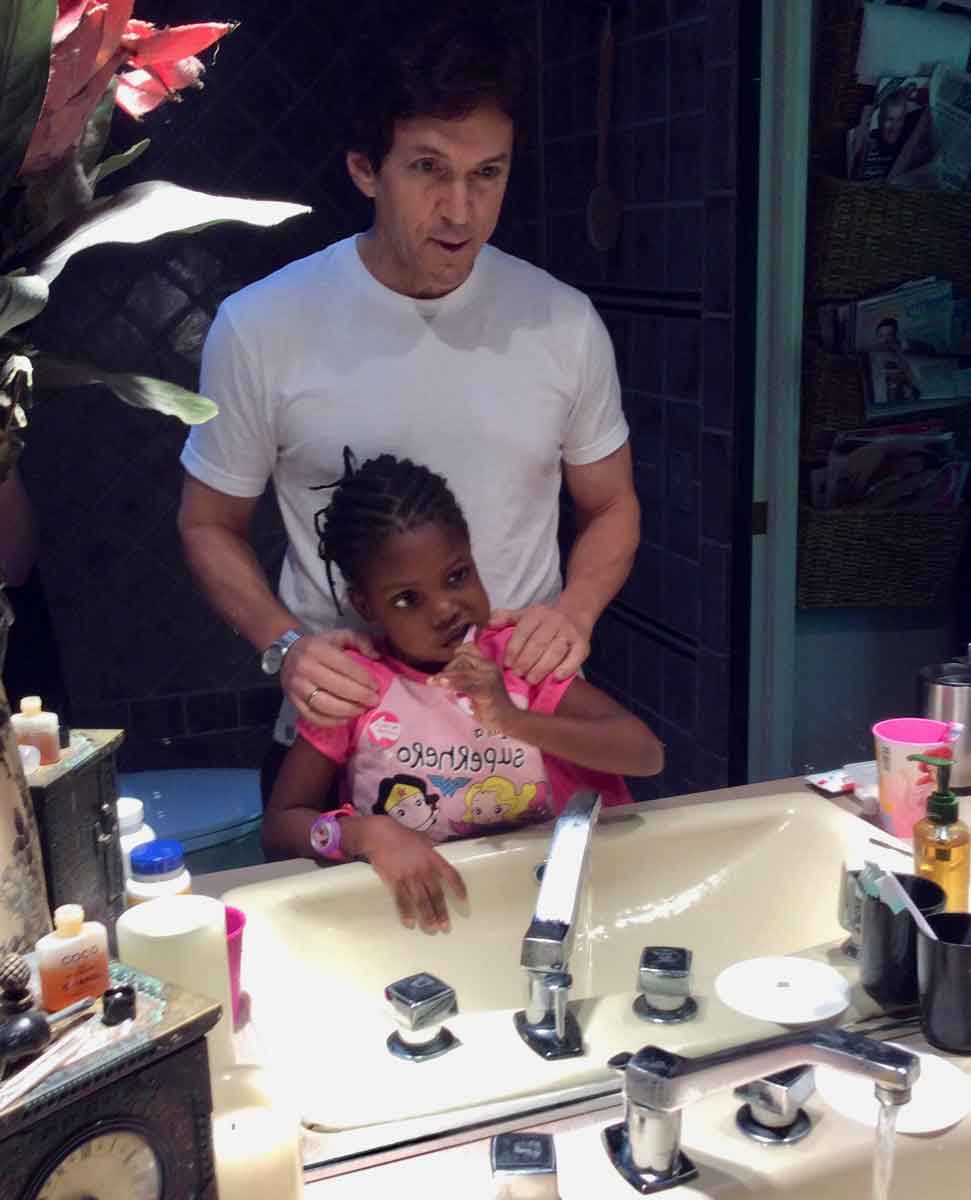

Chika and Janine Albom goof around in March 2016. The early months of that year allowed a small healthier window in Chika’s cancer battle.

Chika’s affection, reserved when she first arrived, was full-bore now. She regularly hoisted herself into our bed and snuggled between Janine and me. She knew, when visitors came, to give the “two arm hug.” And the more cartoon movies about princesses she watched, the more fascinated she became with kissing.

Sometimes, in the early mornings, I’d be down in my office and my cell phone would ring. The house line was calling.

“Mr. Mitch?” came her voice, still froggy with sleep. “Do you want to play fluffy cozy bed camp?”

And I would tramp upstairs, enter the bedroom, and see two lumps under the blankets. Forgetting about writing, I would crawl beneath them and tussle a giggling Chika, who promptly informed me that, “I am the boss, and Miss Janine is the second boss. You can be the third boss.”

She passed her sixth birthday with a celebration at the Rain Forest Café, and more than 30 people came out — friends and relatives who helped entertain and care for her. She drew cards for them. On Valentine’s Day, she drew one for us, with a small figure (her) standing beside two bigger figures (us). It read: “I love you Mr. Mitch, Miss Janine, CHIKA.”

Whoever she encountered was instantly taken with her. Once, while in a Belleville Cracker Barrel with our friends, Jeff and Patty Alley, Chika’s enthusiasm caught the attention of Michigan football coach Jim Harbaugh. He had no idea who she was – and she certainly didn’t know him – but he was so taken with her, he bought her a toy guitar.

She had that effect.

Her voice was magnetic — people actually stopped and complimented us on how sweet she sounded — and she was unafraid to use that voice to blurt out her growing immersion into English, even when her signals got crossed.

Examples? When she washed with cold water, she declared, “Cold water, warm heart!” When I said I was bad at coloring, she said, “You never know since you try.”

She couldn’t get the word “rewind” right, so if I zoomed too far with the remote control, she’d say, “No! You have to remind it!”

She insisted the “Itsy Bitsy Spider” was the “Isby Bisby Spider” and the Mary Poppins song went “Do-a-deer, an e-mail deer.” When she ate something she liked — which was all the time — she yelled “Yummy-yum- my-yummy in my tummy, tummy, tummy!” and when she got dressed or used the bathroom it was “Privacy, please!” If she got testy, I’d say, “Remember, nobody likes a grumpy girl.”

“Nobody like a grumpy boy, either!” she’d shoot back.

Once, while I was writing, she interrupted me multiple times to ask for crayons. I turned to her, patiently as I could, and said, “Chika, I have to work.”

“Mr. Mitch,” she replied, “I have to play.”

Janine and I made all the joyous stops with her, like one of those happy montage scenes in a movie. We took her to a musical, to Disneyland, we took her to “meet” Daniel Tiger. I took her for her first sled ride, which terrified her until she completed it and quickly yelled, “Can I do it AGAIN?” We hit the aquarium, the mall. We bought her a frilly yellow dress, a replica of the one Belle wore in “Beauty and the Beast.” She tried it on in front of a mirror and stared at herself for a long time.

“You’re a princess, Chika,” Janine said.

Chika beamed.

And when she did, it was possible to think, even with a tumor the size of rubber ball sitting in her brain stem, that this child was going to be an exception, that she would push through and live to wear an adult version of that dress one day. This is what children do. They make you believe their youth can overcome anything.

Then one day, she was swimming with an instructor, and I was on my way to work, and my phone rang and it was Janine. She was frantic.

“Chika just threw up in the pool,” she said.

I sped back home. Honeymoon over.

In a hotel room in New York City in February 2016, Chika, 6, tries on her fancy, frilly dress that is a replica of Belle’s dress from “Beauty and the Beast.” She stares at herself for a long time in the mirror. It was her favorite dress. “You’re a princess, Chika,” Janine Albom tells her. And Chika beams at the compliment.

* * *

We never hear from her father. According to the godmother, Herzulia, he is alive, but hasn’t been interested in his daughter since the day his wife died. She says he drinks. All the time. I cannot verify this. I have never met him.

On a monthly trip to Haiti, I ask Alain whether he thinks he can locate him.

“I can try,” he says.

He makes some phone calls. He drives off in the mission car. Hours later, he returns with a short, mustached man, wearing gray slacks and a long-sleeved white shirt in the oppressive heat. Chika’s father. When I ask how he pulled this off, Alain shrugs. He says he made some inquiries, found a village, found the man and asked him to come.

Only in Haiti, I tell myself.

His name is Fedner Jeune. He is maybe 5 feet 7, slightly built. His large eyes are bloodshot, but they are Chika’s eyes. He looks like an unhappy, grown-up, male version of her. When I greet him, I feel empathy and resentment.

Tell him I’d like to know more about his daughter, I say.

Alain does. He responds in Creole.

“He says whatever you want to know, he will tell you.”

I ask questions. About her birth. About her mother. I ask if he can take us to where Chika grew up. He says yes. We get in the car. He is missing two of his lower teeth. He never looks me in the eye.

We drive for an hour, beyond the traffic-choked maze of Port-au-Prince, teeming with street vendors and women carrying baskets on their heads. We reach the out- skirts, where vegetation replaces buildings and paved roads turn to mud.

Alain stops the car.

“We are here,” he says.

A tin door is hinged to a tree trunk. Inside, a patch of earth surrounds a small, square, cinder-block house, which is doorless.

This is where Chika was born? I ask. “Yes,” he says.

There is an extension cord that comes through the breadfruit trees. A single light bulb is hooked to it.

And Chika’s mother died here, I ask?

“Yes.”

Where is she buried?

He points outside.

Can we go? I ask.

In a few minutes, we are at the site. I was expecting a cemetery. Instead, it is just a clearing, dotted by bushes and an old shack made of wood and tin. Laundry hangs on tree branches, and a woman and her children sit on buckets, watching us silently. A goat and a pig wander loose.

Several slabs of concrete, each a different size, are above the ground beneath a clothesline. Fedner points to the biggest one.

“There,” he says.

She is buried beneath that? I say.

“Yes.”

With others?

“Yes.”

How many others?

“I don’t know.”

It is a mass grave. There are no markers.No names.

He pays someone every year, he says, to rent the space.

The goat bleats. Fedner scratches his head. I can tell he wonders why we are bothering with all this. I ask Alain to explain how sick Chika is, and how we hope we can find a cure for her tumor, but it is possible we may not.

Fedner has no reaction.

“If Chika dies,” Alain asks him, “Do you have any wishes where she should be buried?”

He looks down and mumbles something. What did he say, I ask?

“He says whatever you decide is fine with him.”

A bug whizzes by my head. I study the slab above the mother’s remains. I promise myself it won’t be anything like this.

MAY 2016

The tumor, it turns out, was like a sleeping bear: After winter hibernation, it grew hungry and stirred.

Chika’s eye drooped again. Her walking grew unsteady. February, March and April saw numerous medical maneuvers. A drug called Afinitor (Everolimus) was introduced, followed by Avastin, designed to shrink back some of the tumor growth. A new chemotherapy drug called Panobinostat — hailed as promising against DIPG by a Stanford physician — was procured by Dr. Robertson. Chika was approved to receive it and we braced ourselves to enter the “chemo” world. We were following a regimen of multiple nutritional supplements, mixed into a daily shake that Chika dutifully drank from a large princess cup.

Chika, 6, and Mitch at home in Michigan in April 2016. Once she asked him why he had to go to work. When he told her it was his job, she replied: “No, it isn’t. Your job is carrying me.”

Prior to that, desperate to stay ahead of the tumor’s progression, we’d enrolled in a second CED treatment at Memorial Sloan Kettering. The initial procedure again went well. But in the middle of the night, with the catheter locked in her skull and the radioactive iodine oozing into her tumor, Chika somehow got out of bed and walked over to where I slept in a chair.

I heard a noise. My eyes sprung open. There was Chika, inches away, the line from the catheter stretched like a kitchen phone cord.

“Can we go to the toy store?” she asked, dreamily.

I lurched her back toward the bed, the cord retracting. “Oh, my God, Chika,” I said. I frantically called the nurses. It was nearly 4 a.m.

When Dr. Souweidane rushed in, he was, like the rest of us, in virtual disbelief. But apparently, after careful review, no damage was done.

An hour later, Chika was sleeping, Dr. Souweidane was gone, the nurses were tending to other patients, and I was shaking my head.

The toy store?

* * *

She has trouble walking now, and I hold both hands and guide her up and down staircases.

“Step, step, step,” I say.

“Step, step, step,” she repeats. Sometimes she wobbles and lands on her rear end. She does not cry. She’ll say “Woops!” or “Hey, I fell on my butt!”

I find myself learning from her simple joys. She is just so content. She makes the bed for her dolls. She delights in brushing Janine’s hair. On airplanes, she takes things from the snack basket and meticulously tucks them away for later, happy as an industrious squirrel. She claps at the end of family movies. She shimmies when she hears music. When I can’t remember the words to a movie song, she exclaims, “You didn’t watch Mary Poppins before? Are you CRAZY?” I apologize and she says, “You just have to watch it again. No problem.”

During the day, she is joyous when occupied. She colors. She reads. She watches Bible stories. But at night, when I tuck her in, I can see the illness bothers her.

“When am I going to walk right?” she asks.

I hope soon, I answer. That’s why we’re going to the doctors.

“Mister Mitch?”

Mmm?

“If I can’t walk, can I still live with the other kids?”

Of course, I say.

This breaks my heart.

Chika, I say, do you know how much I love you?

She shakes her head no.

This much, I say.

I hold my arms out and grunt as I stretch them behind me. I turn to show her. Suddenly, I feel her hands pushing mine even closer together, closer, until the fingers touch.

“That much?” she says. That much, I say.

JULY 2016

Over the months, we lost track of how many needles Chika absorbed. Her veins were extremely hard to find, hiding as if they knew what was coming. Nurses tried her arms, wrists, feet, toes. Warm compresses. Vein finders.

Nothing helped. Every blood test was a major struggle. Chika was like a pincushion, and she howled with every poke, more scared — like most kids — of the second needle than the first.

Finally, in late June, an Avastin treatment had to be canceled because they could not get a clean vein for infusion. Janine and I were advised that, in order to continue, she would require an intravenous port.

“No! I hate that idea,” Janine said. I agreed. A foreign chamber placed under the skin? With a catheter into a vein that travels to the heart? It was frighteningly futuristic, a permanent branding. But in the end, we had no choice. It was that, or no more medicine.

The procedure was done at Mott (“We do thousands of these” we were told) and once she got home, Chika studied this new addition to her upper chest. She called it her “bump.” We told her it meant “no more stickies,” which seemed to appease her.

As a reward, I promised her another trip to Haiti, after her first port infusion. She endured that.

And the next day, we left.

But something seemed off. Just hours after our arrival at the mission, Chika’s forehead was hot. She looked tired. She wanted to sleep in her bunk bed with the girls, but I suggested she spend that night with me.

After brushing her teeth, and putting her on a pillow, I lay down next to her and shut my eyes.

“Mr. Mitch?”

“Yes, Chika?”

She vomited all over me.

She started to cry. “It’s all right, Chika, it’s fine, this is nothing,” I said, wiping the mess with the sheets. “Here we go. Here we go.” I hurried her to the bathroom.

Thirty minutes later, having cleaned the floor, the bed, changed her clothes (and mine) and put her back onto the pillow, she called my name once more. Her chest was heaving. I turned.

She vomited again.

It happened two more times. I ran out of towels and put old T-shirts beneath us. She finally fell into a troubled sleep, while I stayed awake, monitoring her breathing, hoping this was a stomach bug and fearing far worse.

The rest of the trip was a blur. Chika was mostly groggy, rarely engaged, sleepwalking through events that would normally have her giddy. She didn’t play. She hardly sang during devotions. When we left for the airport, she didn’t even want to say good-bye to the other kids. She just got into the SUV and looked out the window.

She slept much of the ride home.

Within a day back in Detroit, she’d developed a raging fever. We raced to Beaumont Hospital and then, via ambulance, she was transferred to Mott. An infection of some kind, they said. Antibiotics were started. CT scans. PT scans. MRIs. Her temperature zoomed above 104. Her heart rate reached 160 beats a minutes. They thought it was her lungs. They checked for meningitis. They spoke of sepsis. We fell into a nervous vigil in the hospital room, sleeping in chairs, eating from the cafeteria, bringing in balloons to try to brighten the drabness.

In the end, the infection was traced back to the port. Somehow, bacteria had entered during the one time they’d used it. The device was removed (a month after its insertion) leaving a scar on Chika’s soft chest and endless head shaking from Janine and me.

“I knew it was a bad idea,’’ Janine said, near tears. “I knew it. I knew it.”

Now, we were informed, even as Chika lay groggy, sweating, pumped full of antibiotics, that she needed a new form of delivery. A PICC line was suggested (Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter) a long, thin tube that goes through an arm vein and, as with the port, tips into a larger vein that goes to the heart. But unlike the port, a PICC protrudes, hanging from your biceps like a marionette string; it needs to be constantly cleaned and protected.

Again, what choice did we have? The line was put inside Chika and we were given a crash course in how to use it, flush it, sanitize its tips, seal, tuck, then repeat the process.

We hid our frustration. Chika had been through enough. The night before she was to leave the hospital, we all watched a Cinderella movie on the room’s TV set. She loved to see Cinderella dance with Prince Charming.

“You can dance that way at your wedding,” Janine said.

“If I marry a prince?”

“Maybe.” Janine knew Chika’s best friend in America was one of our nephews, a sweetly-tempered 8-year-old named Aidan. “Maybe if you marry Aidan,” she said, teasingly.

Chika frowned and shook her head.

“Aidan will not marry a sick girl.”

“What?”

“Aidan will not marry a girl who cannot walk.”

We were stunned.

“Chika. Of course he would.”

“Aidan will not marry a girl who is missing her hair.”

“Sweetheart. You marry people because you love them, no matter what their problems. Don’t say things like that.”

She looked at us blankly, as if these were the facts that we were too naïve to accept. With a tube sticking out of her arm, she turned back to the screen where Cinderella was dancing, a fairy tale more comforting than the truth.

After a blood infection in July 2016, Chika, 6, lays in bed surrounded by her dolls at Mott Children’s Hospital in Ann Arbor. The infection was traced back to an intravenous port that was inserted. It was then removed.

* * *

The infection puts a hold on everything — including the chemotherapy she had started. It also shoots a hole in our confidence. The chemo is, at best, a long shot. Chika has already endured a second radiation therapy — something considered risky, but that we still tried. Any more radiation could damage her brain and possibly kill her.

We are running out of options, as if someone is crossing them off a list and saying, “Nope.”

Reluctantly, I return to the Internet. There are studies going on worldwide. Experimental drugs. Experimental trials. Each morning, I make calls and leave numbers. I send e-mails around the globe. Everyone wants to know what stage “the patient” is in, and when I detail what she has already been through — brain surgery, two radiations, two CEDs, chemo — a number of places say she is too deep into conflicting therapies, or, worse, just too far along. Every denial is like a chiming clock.

I speak with Tammi Carr. She has offered to help. Her son, Chad, after a courageous battle, died of his DIPG, two months after that game at Michigan Stadium.

“Chad gained his angel wings,” Tammi had written on her Facebook page.

Fifteen months from diagnosis to death.

Chika is at 15 months.

“I know someone in Bristol,” Tammi says. “Bristol” is Bristol, England — just as “Houston” is the MD Anderson Cancer Center and “Mexico” is the intra-arterial treatments they are trying in that country. DIPG has a code of its own; all parents seem to know the shorthand.

The Bristol program is similar to Sloan-Kettering, but instead of putting one catheter into the brain tumor, they use four. I correspond with the doctors there. I send scans through overnight delivery. Eventually, Chika is determined to be too far along (those words again). The doctor suggests an immunology program in Cologne, Germany.

Germany?

E-mails are sent. MRIs are sent. A Skype session is arranged. Chika qualifies. It is $45,000 for the treatment, no insurance taken, and at least three visits are required over three months time, eight days per visit, to judge the procedure’s effectiveness.

Place your bets.

SEPTEMBER 2016

The Cologne clinic’s technique uses the patient’s blood to create a vaccine to attack the cancer.

I pulled Chika’s wheelchair backward, up the small ramp and into the three-story apartment building in Cologne. A trolley rolled past. Passengers unloaded, students chatting loudly in German. We’d rented a flat here, and had been in it a week.

“I have to go potty,” Chika moaned.

“Hang on, hang on,” I huffed. I undid her belt, lifted beneath her arms, hoisted her onto my shoulders and clomped up a 20-step staircase. There was no elevator in the building.

“Hang on, hang on,” I said, my breathing labored.

“I have to go baaad.”

“Hang onnnn.”

I fumbled with the keys. I opened the door. “Hurry!”

Into the bathroom, jacket off, leggings yanked down, hoist her onto the seat.

“OK? OK?” I said, panting.

“Privacy, please,” she replied.

Out I went. In came Janine. This was our routine now. Chika had regressed from a walker to a wheelchair. For short distances she crawled across the floor. “My feet are sleepy,” she would say.

She had increasing issues with her bladder. Bathroom runs were a fire drill. Sometimes we found her quietly sobbing in the morning, and we’d say, “What’s wrong?” and we’d see the wet sheet beneath her and she’d say, “I need new underwear.”

Her left eye no longer blinked, and at night we put soft tape over it to keep it from drying out. Her PICC line required constant care, robbing her of her beloved swimming or bubble baths. She could no longer pedal a toy car or run to hide behind a couch. We prayed that this immunology treatment would be her miracle. But the laundry list of things she had to surrender was growing longer than things she could do.

And yet. Her adjustment skills were incredible. We’d sit and watch a film and she’d get so happy she’d throw her arms around me and say, “This is a really good movie!” I’d ask her what was her favorite part and she’d say, “Um, I don’t really understand what’s happening.”

Or in Germany, in a small apartment, where we had to sleep in three twin beds pushed together. Chika loved it. She flopped between us as if we were pillows, asking Janine and me to kiss so she could watch. When we did, she clapped and said, “Now we can live happily ever after.”

Chika, 6, and Mitch Albom in front of the Cologne Cathedral during a trip to Germany for an immunology treatment in September 2016.

Every day, after her treatments, we’d explore the streets of Cologne, me pushing her in her wheelchair, Chika flapping her arms and singing out loud, butchering lyrics from “Annie,”, “Frozen” or Christmas songs (“down through the chimney comes old, sick Nick!”). She remained totally unembarrassed. I envied her bravado.

I wheeled her once to the towering Cologne Cathedral, first built in the 13th Century, and she surveyed it from her wheelchair and said she had never seen a building so big. I told her it was a church and that people prayed inside it.

“What do they pray for?” she asked.

“They pray for everything. They pray for their family. They pray they’ll get better if they are sick.”

“They don’t pray for me. I’m not their child.”

“They might be praying for you.”

“They don’t even know me.”

“People don’t have to know you to pray for you.”

She thought about that, then went back to chewing on a pretzel.

Chika was no stranger to faith. Sunday church and nightly devotions are routine at the Haiti mission, and she was always a loud and joyous force during those prayers. In Michigan, Janine once walked in on her intently singing a worship song to herself.

“I’m no longer a slave to fear,

I am a child of God…”

She sang it, uninterrupted, for nine minutes, as if in a private discourse with the Lord, her face calm, her eyes wide.

“I’m no longer a slave to fear

I am a child of God.”

One night, she asked if her mommy was in heaven.

“Yes, she is,” we said.

“When I go to heaven, will I see her?”

“Yes.”

“How will she know me?”

“She’ll know you.”

“Can you walk in heaven?”

“Yes.”

“Can you run?”

“Yes.”

“Can you have candy?”

“Yes. Why?”

She shrugged. And then it hit me. She was listing all the things she could no longer do down here.

* * *

Of all the maddening aspects of cancer, the worst may be the deal it seems to make with our immune systems. While our T-cells regularly attack other infections, cancer employs what some call a “secret handshake” that renders T-cells blind to their threat.

“Immunotherapy” is a treatment that tries to alter that handshake — often by fooling the immune system into fighting the cancer. The Cologne clinic that treated Chika (called IOZK, and run by a Belgian oncologist) employed a technique that uses the patient’s own blood to create a cancer-fighting vaccine. This is done through the injection of a virus (NDV) that is deadly to poultry but harmless to humans. It attacks the DIPG tumor, the attack is studied, dendritic cells are beefed up in a specialized laboratory facility, and, ultimately, a vaccine from the patient’s own white cells and tumor antigens is injected back into the body, with the hope that the immune system does what the virus did: attack and kill the cancer cells in the brain.

Chika, again, didn’t understand any of this. But she listened to the doctors speak “a funny language” and she liked the water bed they let her lay in. The clinic was sparse, simple, on the fourth floor of an office building, one level above a gym. We sat near Chika as her head was heated by hyperthermia, and the poultry virus dripped through her PICC line, while she watched an iPad movie, lost in the magic of “101 Dalmations.”

A nurse brought me a cup of coffee. I heard conversations in German. I thought about how far we were from Haiti, and our kids kicking a soccer ball in the yard, wondering where Chika was and what she might be doing.

* * *

I go to a doctor. I’m having pain in my lower abdomen. I may have a hernia.

“Are you doing a lot of lifting?” the doctor asks.

I almost laugh. Chika is constantly in my arms, and even at 62 pounds, is a challenge to pick up from funny angles.

Yes, I tell the doctor, a lot of lifting.

“That could do it,” he says.

He says I should stop, but I know I will not. Holding this little girl, her arms hooked around my neck, head cradled beneath my chin, is the most satisfying posture I have ever known. I can feel Chika relax, feel the security that she gets from my grip. I try to find the word for it.

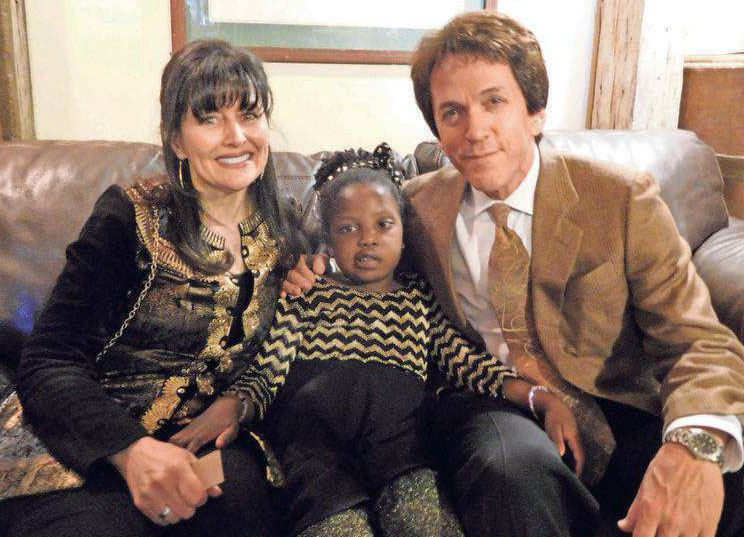

Janine, left, Chika and Mitch at a family wedding in Michigan in October 2016.

Trust. That’s the word.

Total, unconditional trust.

One night I carry her to her bed, and I lay her down and she looks up sweetly. Janine is there, too.

“How did you find me?” she whispers.

How did we find you? we say, surprised. You mean how did you come to us?

She nods.

We look at each other. It is the first time, really, she is asking who she is.

So we tell her. Her birth. The earthquake. Her long journey to this moment. When we finish, she seems satisfied. “One day,” she says. “I want to go back and live in Haiti.”

But if you weren’t here, we would miss you very much, we say.

“Well,” she responds, “when I’m not here, you can close your eyes and think of me!”

And while we cannot imagine life without her, the truth is, we would surely take this, if it meant she could grow, if she could live out her years, seeing adolescence, graduating high school, finding a purpose, realizing her dream of being, as she once wished, “big.”

We would take it in a heartbeat.

DECEMBER 2016

Chika and Janine on Christmas morning in 2016 at home in Michigan. Chika had wanted to celebrate in Haiti, but a severe setback with her tumor made travel impossible.

There was no joy at Christmas. Chika had suffered what the doctors euphemistically called “a setback.”

Upon returning from her third trip to Germany, she was sluggish, her left side showed weakness and she threw up several times. She was drooling and her speech was slurring.

We returned to Mott. They took an MRI. The worst news was confirmed.

The tumor had sharply progressed.

This is the moment DIPG families dread. They are warned. They are briefed. Still, when it happens, it is like a sneak attack. I spoke with other parents. One told me his DIPG son was walking and talking and a week later, he was gone.

For the first time since Alain’s phone call, I began waking up in fear.

Chika’s eating grew labored. Her drinking, too. Her right arm and hand weren’t really functioning, and when I gave her cups, she bobbled them and they spilled.

“Oops,” she’d say, quickly. “Sorry.”

“It’s all right, no problem,” I’d reply, putting a cheer on every sentence.

But when your child’s outlook changes, your world changes with it. There was no personal time any more. Projects were tabled. Work meetings were canceled. I all but stopped writing for the newspaper. Janine and I wore floppy clothes around the house, showered less frequently, and almost never went out socially. The normal Christmas stuff was put on hold. No shopping. No gatherings. Instead, we spent nights monitoring Chika’s breathing, getting her to the bathroom on time, sitting with her as she tried to color, frustrated that her shaking hands could not stay within the lines.

She lost a tooth one night and, as was custom, she put it under her pillow for the Tooth Fairy. But we were so exhausted from giving her medicine, flushing her PICC line, and feeding her through syringes (which took hours, because she could no longer swallow whole food) that we fell asleep that night without tending to the matter.

In the morning, we found Chika sitting up, her head bowed, the tooth in her hand.

“Chika, what’s the matter?” we asked. “The Tooth Fairy forgot me,” she mumbled. Our fall was complete.

On Christmas Day, we woke her up, and dressed her in a red sweater. We tried to stir her interest, but she was groggy, her eyes blank. We sat her by the tree and slid in one present after another, gifts people had brought for her. She responded slowly, lacking any thrill of a year earlier, when she ripped open everything.

In the middle of this, Janine leaned over and gave her a kiss. Then she asked, “Do you want to kiss Mr. Mitch?” She nodded and kissed my cheek with a spitty smack. Then Chika whispered, “Kiss each other.”

So we did, in front of her face, and she had a look of wonder, and Janine started to cry and said, ‘Thank you, angel.’ And with her good hand, Chika reached for the tissues and pulled one out and tried to dab Janine’s tears, which only made her cry more.

* * *

The disease progression is like death by a thousand cuts. But the hardest loss is Chika’s voice. That precious voice, like cotton candy melting in the air. When it begins to fade, I am desperate to hang on to its sound.

Chika gets help from physical therapists Shruti Joshi, left, and Mia Grimes in January 2017 at Walk The Line To SCI Recovery center in Southfield.

Good morning, Chika, I say.

No response. Just a stare.

Good morning, sweetheart.

Nothing.

She sleeps with many dolls now, so I take one, a small bear, and ask it questions, hoping to engage her.

Do you belong to Chika? I ask the bear.

“Yes,” Chika finally whispers.

Ah. You’re a lucky bear. I think Chika is a really special girl. But don’t tell her! That’s just between you and me.

“But … I’m her bear,” she says. “I have to tell her everything.”

Oh, really? Well. I don’t want you to tell her how much I love her.

“She knows.”

She does? How much? How much do I love her?

Chika slowly takes the arms of the teddy bear and pulls them behind its back.

“This much,” she whispers.

I choke up.

That’s right, I say. That much.

Chika and Mitch share words on her seventh birthday in January 2017. By this point, she was wheelchair-bound. Within weeks, due to the tumor’s surge, her sweet voice would be gone.

FEBRUARY 2017

Nurses had arrived in our home. Hospice workers, too. Rehab was arranged, where therapists worked Chika’s otherwise motionless appendages. A support team of friends and family combined for 24-hour shifts. And Chika made a trade. Her PICC line was removed, because of swelling in her arm.

And a feeding tube was inserted.

Above her belly button, just below her sternum, a tiny balloon was pushed through her skin topped by an exposed valve that was connected to a tube. Through that tube, you could drip almost anything — water, apple juice, smoothies, drugs.

We had to use it, because Chika’s swallowing was gone. Her speaking was gone. Her voluntary movement was limited to a finger wave — all because of the relentless DIPG tumor rooted in her pons and spreading like an ooze, slowly crippling her every ability. Germany was out. So were any return trips to Haiti. Chika could no longer endure the travel. I was almost grateful that she couldn’t ask to go home, because I hated having to disappoint her.

She’d thinned considerably, and with her hair braided, she looked younger, remarkably like the day she’d arrived, except for the 4 inches she’d sprouted, seemingly all in her legs. A hospital bed had replaced her previous one, and she slept just 2 feet away from us now, close enough to hear every breath. The pulse/oxygen monitor was placed on her finger, and small red digits were a constant reminder of her status. If they dropped, we needed to do something: tap her chest, pound on her back, put a suction tube down her throat and pull up whatever was clogging it.

Because so much of this felt barely human, we did all we could to humanize the rest. We read to Chika. We sang to her. We recited a special prayer. Each night, we Skyped with the kids in Haiti as they sang their devotions, and one by one, they stepped before the camera and said “Good night, Chika,” “Good night, sister.”

She responded to their voices like Tinkerbell to pixie dust. I hated to cut off the connection. Sometimes she looked at me silently, and I remembered fixing her toy, and I could almost hear her say, “Can’t you fix this? You’re the grown-up.”

It haunted me.

Mitch spends a moment with Chika in her bed in February 2017. Her swallowing was gone and her speaking was gone as the tumor slowly crippled her abilities.

For the first time in my career, I missed the Super Bowl, because Chika was throwing up the morning of my plane. I canceled all commitments. I stopped answering the phone. Our entire focus was on prolonging Chika’s life.

She was a fighter.

We would be fighters.

Our medical Hail Mary was a drug that few had heard of, Buparlisib, or BKM120, technically a “pan class phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor.” We understood it only as something that might stall the tumor growth, because Chika’s specific tumor mutations, on paper, matched up to this agent. It was nearly impossible to get. Numerous pleas were made to Novartis, the Swiss-based global health care company, to grant us the drug (not available to the public) through its “compassionate care” program. Although we were turned down several times, with help, we ultimately were granted a supply. Each morning, Janine and I opened the little capsules and dissolved them into water, then pulled the water into syringes and pushed it through Chika’s feeding tube.

Janine and I did this silently. Carefully. Neither one of us wanted to say what we were thinking: that we were out of chips, the last bet had been placed.

Sometimes, when we sat with Chika, I thought about how, in a certain way, was growing backward, toward infancy. She’d gone from running to walking to crawling to being lifted. From eating to being fed. From bathrooms to being wiped.

From talking to silence.

She was, in a strange way, returning to where she started.

So far from where she started.

* * *

I arrange a one-day trip to Haiti.

I have to purchase a grave.

The laws, I am told, require proof of interment arrangements before a body will be allowed to come into Haiti. I long ago decided that if things went badly, she would be buried here, in her home country, where one day the other children could come and visit. But I cannot fathom making these arrangements if Chika dies, and so I do it now, while it still seems abstract.

Alain drives me to a cemetery called Parc Du Souvenir on the outskirts of Port-au-Prince. I am told it is the nicest one. But in comparison to an American cemetery, it is only fair, the graves in uneven rows, plain white headstones, erratic plantings.

I find two empty sites together. We go to the office and Alain informs the manager, a broad-faced, middle-age woman, that I want to purchase them.

“For how many people?”

One, I say.

She almost laughs.

“One person, you should use the crypt in the wall. A grave is for five people.”

Alain explains that in Haiti, bodies are stacked five high in grave sites.

“Two would be for 10 people,” the woman adds.

Well, I want two plots, I repeat. I want space for her loved ones to be able to sit and visit.

She shakes her head as if I am crazy. “Who is it for?” she asks.

I don’t want to tell her the whole story.

My daughter, I say.

She looks at me.

“I’’m sorry,” she says.

APRIL 7, 2017

The phone rings. No one answers it. This is back where the story began, in our bedroom, on a Friday afternoon. Our friends and family have said their good-byes, exiting in tears. It is only Janine, the nurses, me.

And Chika.

We surround her in the bed. We want to “cuddle” her, a word she loved, to hold her in our arms for her final hours. We are trembling. Her breaths are so infrequent. There’s one, we say. We were told that when the end came, it would be like this, the brain no longer sending the proper signals to breathe. It sounded chaotic. But it is not that at all. It is slow, gradual, like watching a sun disappear over the horizon.

We have surrendered, I hear my inner voice say. I feel like a failure. The day before, Chika’s breaths had slowed like this, she was down to one or two a minute, and we leaned on her tender body and the hospice nurses who had been called confirmed that this was likely the end.

But Janine heard a small sound, and another one, and said out loud, “It sounds like she’s trying to breathe.”

We heard it again.

“If she’s trying, we’re trying,” I insisted.

And so we propped her up, tapped her back with soft rubber pounders, suctioned her throat and nose. And rather quickly, Chika was breathing 33 times a minute. She’d literally risen from the almost-dead. The hospice people shook their heads in disbelief.

“She’s unlike anyone we’ve ever seen,” they said.

And she was. She always was. She was strong and stubborn and so filled with life that even a killer tumor struggled to suppress it. The doctors who predicted a quick demise were stunned by her longevity — 23 months is an eternity with DIPG — and her Michigan doctors said they learned things from her German doctors and her New York doctors and the drug interactions and the immunology we tried. It enlightened them to new ways of looking at this disease.

“She’s taught us all a few things,” admitted Dr. Ken Pituch, the director of Mott’s palliative care team.

And yet, she is only human.

And the cancer is not.

The sun is strong outside. Soft prayer music is playing through an iPad. Suddenly, for no apparent reason, Janine asks for a stethoscope. She has never done this before. Something about the moment makes her want to listen.