A Teacher to the Last

Tuesdays with Morrie

‘A TEACHER TO THE LAST’: BATTLING FATAL ILLNESS, A PROFESSOR USES DEATH TO SHOW US HOW TO LIVE

November 12, 1995

BOSTON — The worst part of dying this way, he said, was that he couldn’t dance. Morrie loved to dance. For years he went to a church hall not far from Harvard Square, where once a week they would blast music and open the door to anyone, dance however you wanted, with whomever you wanted. Morrie danced by himself. He shimmied and fox-trotted, he did old dances to modern rock music. He closed his eyes and fell into the rhythm, twirling and spinning and clapping his hands. There, among the college students, this old man with twinkling eyes and thin white hair shook his body until his T-shirt was soaked with sweat. He was a respected sociology professor with a wife and two sons. He had written books. He had lectured all over. But on these nights, he danced alone like a shipwrecked child. He wasn’t embarrassed. He never got embarrassed. For him, the whole thing was a sort of introspective journey.

It would not be his last.

Dancing ended for Morrie Schwartz in the last few years, as did nearly every other physical activity; driving, walking, bathing, going to the bathroom, even wiping tears from his eyes. He was hit with Lou Gehrig’s disease, a killer that takes the pieces of your life the way a dealer takes the cards off the blackjack table. Your nerves die, your muscles go limp. Your arms and legs become useless. Even swallowing is a chore. By the end, the only thing untouched is your mind. For most people, this is more a curse than a blessing. Most people.

“My disease,” Morrie once said, lying in the chair in his West Newton, Mass., study, “is the most horrible and wonderful death. Horrible because, well, look at me” — he cast his eyes down on his ragged, shrunken body — “but wonderful because of all the time it gives me to say to good-bye. And to figure out where I’m going next.”

“And where is that?” he was asked.

He grinned like an elf.

“I’ll let you know.”

The art of dying

This is the story of a small, courageous man, who was handed a death sentence and decided, rather than retreat, to take everyone with him, right to the final step, to descend into the dark basement and yell back over his shoulder why we shouldn’t be afraid. It was a decision made initially for those closest to him, his wife, his sons, his colleagues at Brandeis University, and his students. He didn’t want them to shun him, or to feel sorry for him. So he transformed his horror into something familiar. He made dying his final class.

He wrote every day, while his hands still worked, until he had 75 reflections about living with a fatal illness. He taught these to classes and discussion groups who crowded in his house. He spoke about accepting death as part of nature, about maintaining your composure, about using death as the ultimate lesson.

“Learn how to die,” he said, “and you learn how to live.”

Before it was over, his message would spread from that quiet house in suburban Boston to the farthest reaches of the broadcast world — thanks largely to three appearances with Ted Koppel on ABC’s “Nightline.” Koppel, like most visitors, met Morrie one day and was hooked. After the programs aired, people flooded Morrie with letters, and some actually flew across the ocean to spend a few minutes by his side. As death approached, and he went from a walker to a wheelchair to eating through a straw, some began to see him as mystical, a human bridge between this world and the next. Others simply felt comforted by his smile in the face of our worst nightmare.

As his days on Earth dwindled, his influence grew.

He influenced me.

But then, he always had.

July

My college mentor

“Have a bagel.”

He pushed the plate across the table awkwardly, his fingers flicking like a robot on a weak battery.

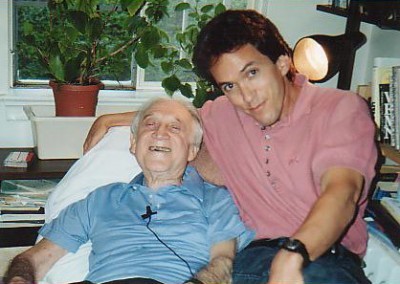

I knew Morrie Schwartz before he ever got sick. He was my favorite professor in college, my mentor, my friend. In my four years at Brandeis back in the ’70s, I spent countless hours in his classroom, or hanging around his office.

“What are you going to do with yourself?” he would ask me.

“Be a musician,” I would answer.

“Fine. Good. But whatever you do, be as human as you can. Never lose your humanity. Don’t be like so many of your fellow students now. All they want to do is make money.”

He shuddered at that thought. A gentle, impish professor who wore yellow turtlenecks, corduroy pants and Rockport shoes — his fashion sense was nonexistent — Morrie Schwartz taught sociology at Brandeis since 1959. He taught about mental health — he had cowritten a breakthrough book in that area — and he taught about human relationships and, later, the nuclear threat. He was one of those teachers for whom the ’60s were the right idea. He loved freedom of expression; he hated greed and war. Once, during the Vietnam era, he gave all his students A’s to help them avoid the draft.

Morrie took me in the way he took in hundreds of confused college kids in his nearly four decades of teaching, serving as adviser, philosopher and surrogate parent. I enrolled in every class he taught. Wrote my honors thesis with him. When I graduated in 1979, I purchased a leather briefcase with his initials engraved in the front. It was the only time I ever gave a teacher a present.

“I love you,” he told me the day I graduated.

“God, Morrie,” I said, embarrassed, “you’re such a cornball.”

He laughed and said that one day, he would get me to open up, maybe even to cry.

A student again

“Have a bagel,” he said again.

“OK, OK, I’ll have a bagel.”

I took a bite, and he smiled, then he lifted his fork gingerly to his mouth. He could only eat soft food now, a vegetable cake and some soup. Chewing was hard. Swallowing was harder. He had health care workers to push his wheelchair and to lift him onto the toilet and back off again. He could no longer bathe himself, and he needed help getting dressed.

“You know the biggest thing I dread?” he whispered. “When I can’t wipe my own rear end. For some reason, that really bothers me.”

He sighed.

“But that’s coming. Pretty soon I think.”

Embarrassing? That was Morrie. No secrets. Nothing off- limits. It had been 16 years since I’d seen him. He was 78 now. When his face appeared on “Nightline” — “Tonight, a college professor teaches us how to die” — I was stunned. I flew in to visit, and he greeted me in a wheelchair, a blanket over his knees despite the summer heat. His hair was thinner and his skin paler than I remembered, but I would have known him from a mile away. The son of poor Russian immigrants, Morrie was blessed with a crescent smile that crinkled his eyes and made everyone feel like family.

“Ah, my old friend,” he said, lifting his hands for a hug.

I hugged him, and felt how thin he had become. There was little meat on his bones. His voice sounded scratchy. Later I would learn that the disease was already quite advanced. Morrie had first sensed something wrong back in 1992, when he couldn’t sleep. Next he had difficulty breathing — which he first attributed to his asthma — then a hard time walking any long distance. Once, at a friend’s birthday party, he tried to dance and he stumbled. Another time he walked up a flight of stairs and had to rest before he could come down.

Doctors kept saying it was a muscle problem. They X-rayed him. They tested his bone marrow. Finally, he found a doctor who suggested it was a neurological problem. Different tests were taken. And a new verdict was reached.

“Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,” the doctor said. “ALS. Lou Gehrig’s disease.”

Morrie remembered the ballplayer from his youth in New York City. He also remembered that he died.

“It’s fatal?” Morrie asked.

Yes, he was told.

Is there any known cure?

No, there is not.

“I had two ways to go at that point,” he recalled now. “I could be angry at the world, want nothing to do with it, say, ‘Why me?’ Or I could say, ‘Maybe this gives me something new to share.’

“I chose the latter. What I’m trying to do is to live as fully and as deeply as I can in my time left. Just because I’m dying doesn’t mean I have to be taking. I can be giving, too.

“You know, some wise old yogi said, ‘Everyone knows they’re going to die, but nobody believes it.’ ”

He raised his eyebrows. “Well, I believe it now. I know I will die. I just want to decide how. Raging? Screaming and kicking? Or maybe quietly, holding the hands of people I love? I’m not sure.” He lifted the cake to his mouth, and chewed in a mushy mess. I smiled to myself. Back in college, we teased him behind his back for the sloppy way he ate. He was so enthusiastic, talking before he swallowed. I still can see him yakking through an egg salad sandwich, the little pieces of spit and egg spraying from his mouth as he talked. He was such a lovable slob. The whole time I knew him I had two overwhelming urges: to hug him, and to give him a napkin.

And here, in the kitchen of his final months, nothing had changed.

And everything had changed.

“So, you’ll come back?” he said, after we’d talked for hours and I readied to go.

“Sure, every week,” I joked.

“OK then, every week,” he said briskly. “For you, I’ll put aside the time. You were always one of the good ones.”

I left, flattered and confused. But I returned the very next week.

And every week thereafter.

I was officially enrolled.

August

‘Life is with people’

The pine trees outside his office window were thick with green leaves. August was steamy. You could hear the lawn mowers off in the distance, and the sounds of children enjoying their summer vacation.

“Close the door, it’s a little cold,” he said.

I closed the door. But it was not cold. Morrie was in his special reclining chair in his office, which, by pressing a button, would rise or drop so his aides could lift him easier. The wheelchair now was difficult to take. His legs were useless, and he couldn’t lift his arms any higher than his face. The cost of being cared for at home was astronomical, and the insurance only covered a portion. So the disease was not only stealing his body, but most of his savings.

Still, he would not go to a hospital. And he would not be kept alive by machines. “That’s not life,” he said. “Life is with people.”

He smiled when I entered — as he smiled every week — and I rubbed my cheek against his soft face. I heard his breathing, which was noticeably labored.

“Still following the news?” I said, noticing the newspaper beneath his reading glasses.

“I try to,” he said.

“Why bother?”

I realized immediately how bad that sounded.

“Well, it’s true, I won’t be here much longer. On the other hand, in a strange way, I feel more connected now to the people in this world who are suffering, the people getting chased out of their homelands, the people being murdered.

“When death is real for you, it’s real for others, too.”

Did any one news story affect him more than others?

“Bosnia. Sometimes, I look at TV and the pictures of those poor people, and I begin to cry and I can’t stop.” Morrie always had been able to feel others’ pain, perhaps because he’d had so much of his own. He was raised in New York, in the back of a Lower Eastside candy store. His father — who would die after being robbed by muggers — worked as a part- time furrier, and made barely enough money to get by.

His mother only survived until Morrie was 8. She was ill and spent most of those years resting on the bed or couch. One day she went to the hospital and didn’t come back. A telegram arrived at the store. Morrie had to read it to his immigrant father.

Mother was dead.

Seventy years later, he still cried.

“It’s why I can never have enough holding or touching now,” he said during one of our visits, as the tears began again.

“Do you know what it’s like, not to have your mother as a little boy?”

He made up for it now with the love of adults. When people learned Morrie was sick, they came to his house as if making a pilgrimage. Colleagues. Former students. Old friends. Morrie’s wife of 44 years, Charlotte, would marvel at the stream of appointments he made, one right after another, someone at 2 o’clock, someone at 3 o’clock, someone at 3:30. She worried for his health, that all the company might drain him, but she also knew it was what he wanted. To talk. To learn. Mostly, to share his experience.

Once, I asked him what he wanted on his tombstone. He thought for a moment. Then he said: “A teacher to the last.”

He looked at me and winked. “Pretty good, huh?”

At moments like that you could believe he would go on forever. But then he’d cough and fight to breathe and you knew that was just a dream.

September

The expanding classroom

“First of all, Ted, before you talk to me, I need to know a few things about you.”

The visitor, Ted Koppel, was taken aback. He was not used to conditions before an interview.

“What do you want to know?” Koppel asked.

“Tell me something from your heart,” Morrie said.

Koppel thought for a moment, then finally talked about his children. Morrie watched him. Nodded slowly.

“Now tell me something about your faith.”

Koppel squirmed. “I usually need to know people a little longer before I share these kinds of things.”

Morrie rolled his eyes over his bifocal lenses. “Ted,” he said, “I don’t have a lot of time here.”

Koppel laughed, and he opened up. This was during their first meeting, in the late spring of this year. The “Nightline” program had learned of Morrie through a Boston Globe article, and Koppel flew to Boston to devote the entire show to him. Morrie, of course, wore no makeup, and did not even change the shirt he was wearing. The show drew a huge rating.

“Nightline” returned for a follow-up. That, too, was well-received. On both shows, Morrie, who held a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago, read some of his reflections, such as:

* Talk openly about your illness with whoever wants to talk with you.

* Seek the answers to eternal questions, but be prepared not to find them. Enjoy the search.

* Be grateful that you have been given the time to learn how to die.

He also said to Koppel, “Soon, someone’s gonna have to wipe my ass” — then asked whether it was OK to say that on television.

After the first show, Koppel shook Morrie’s hand. After the second, he leaned over and hugged him. “I’m breaking him down,” Morrie boasted.

Koppel said he wanted to do a third show, but wasn’t sure when. That was before the summer. Now, as the first breezes of autumn began to blow, the mood around the Schwartz house was more grim. The workers bit their lips when asked how Morrie was doing. No one talked about television.

“I think the ‘Nightline’ people,” Morrie said, his voice now labored with heavy breathing, “are . . . waiting for me to be . . . on death’s door. It’s more . . . dramatic.”

“Doesn’t that make you angry?” I said. “Like they’re using you?”

Morrie rolled his eyes. “If they’re using me, I’m using them. I’m reaching more people than I ever taught before.”

Morrie had sunk noticeably over these weeks. We never ate in the kitchen anymore. His life was down to two rooms, the office and the bedroom. He hadn’t been outside in a long time, and, although I didn’t know it then, he would never be outside again.

Instead, he studied the pine trees through the window, and the small hibiscus plant he had on the sill. He took amazing joy in its pink leaves, just as he took great pleasure in listening to music, opera, mostly. It made him cry. He read books. And he read the mail, letters from strangers wishing him well.

One day he said he had a month to live, and I said he was crazy, how did he know?

He just smiled and shrugged. Several times a week he meditated with a teacher, and, following a Buddhist suggestion, he thought about death a little each day.

“You pretend there’s a little bird on your shoulder,” he said, “and you ask it every morning, ‘Could today be the day I die?’ ”

No time to quit

If all this sounds horrible, Morrie did not see it that way. He saw the whole thing as “a great adventure.” We had decided that all our weekly meetings were too precious to forget, so we began taping them for a possible book. It was Morrie’s idea. “Our last thesis together,” he said.

His diet was mostly liquid now, fiber drinks and juices, sometimes a bran muffin soaked in milk. There was an oxygen machine, which he hated but used to help his breathing. A commode had been moved into the room (it looked terribly out of place among the shelves of serious books and papers) and before the month was up, Morrie would have a catheter inserted, because getting to the bathroom to urinate was too much of a strain. The small bag sat at the base of his chair, filling with waste fluid.

“Does it make you uncomfortable?” he asked.

“No,” I said, lying. Morrie wanted no one to be put out by his illness. He never demanded that his sons — Rob, who lives in Tokyo, and Jon, who lives in Brighton, Mass. — drop what they were doing and spend every minute with him. He never insisted that Charlotte stop working at MIT. “Why should they stop for me?” he said one week. “Then this disease would take four lives instead of one.”

Instead, he took solace in the times he was able to meet with people. And in making up aphorisms about dealing with fatal illness.

“Want to hear my latest?” he asked.

I nodded.

“When you’re in bed, you’re dead.” He grinned. “That’s why I sit in my office.”

One week, I decided I should see everything Morrie went through, no matter how squeamish. I asked whether I could help him when he used the commode.

The worker and I lifted him together and pulled down his loose sweatpants, which peeled away like a husk off a cob. Morrie’s skin was nearly white as chalk, wrinkled and loose. We lowered him onto the seat. His stomach was grumbling and made noises that under other circumstances would have been embarrassing.

But Morrie was unfazed. “Here we go,” he whispered. “Like a baby . . . right?”

Indeed, physically, Morrie was becoming more childlike as he neared the end. He needed to be fed. He needed to be bathed.

And he had lost his battle to wipe his own behind.

“At first I was angry,” he had said about that. “But I knew that anger would get me nowhere. So you know what I did? I decided to embrace my dependence. I decided to enjoy being taken care of, having my hair washed, having my feet massaged, even having my rear end wiped.

“And you know what I discovered? We never get enough of that as children. It’s inside us, the secure feeling of being handled. I chose to revel in it.”

Sitting there, that day, with my old professor on a toilet, still managing to smile, I wondered how any of us could ever complain about anything.

October

No fear

“Hit him harder!” the therapist said. “Pound on his back.”

Morrie was curled on his side, limp as puppet. The therapist was teaching a new worker how to loosen the congestion in his chest. I tried this too, pounding, then letting him breathe, pounding, letting him breathe.

“You . . . always wanted . . . to beat me up . . .,” he croaked.

“Not really,” I said.

Our visits had become shorter, and sometimes we just sat together. Morrie could speak only haltingly, and for maybe a half-hour before tiring. He was taking morphine injections, and he coughed ferociously. I wiped his mouth from the phlegm he spit up. ALS creeps through your body, atrophies the muscles and finally wins when it attacks your respiratory system; it literally takes your breath away. Artificial machinery can prolong life — author and physicist Stephen Hawking has lived in a paralyzed state for 10 years — but without it, death is inevitable.

And the lungs are the bullseye.

“The other night . . . I had a coughing spell . . .,” Morrie said one week. “And I thought . . . that was it . . . I might go right then.”

“Were you terrified?”

“No . . . at first, I felt afraid. . . . But then, I concentrated on the fear . . . and separated myself from it. . . . It was like I was outside the experience . . . and I calmed down.”

Morrie had made up his mind on death. He wanted to go serenely. No kicking. No raging against the night. He wanted his loved ones nearby, and he wanted a quiet passing, without horror for his survivors. He said he feared death less as he got closer, not more.

As for God, a concept he had never really embraced?

“I’m having . . . some second thoughts . . .,” he said impishly. “I hope .. . I get an answer . . . before I go.”

There were so many things we had discussed over the months — society (“we have to think of ourselves as part of one big community or we’re all doomed”), funerals (“what’s the point of everyone saying nice things when you’re gone? I want to hear them while I’m alive.”), even reincarnation (“I hope to come back as a gazelle.”)

Still, as the days passed, and he grew weaker, I felt a terrible void. Koppel and “Nightline” came for their final show. It was perhaps the most moving of all. At the end of the filming, Koppel gave Morrie a kiss.

On the final Tuesday of October, Halloween day, I entered the house. Morrie’s office was empty.

He was in bed.

All his appointments had been canceled. I was the only visitor allowed to see him. He motioned under the blanket and I reached in and found his hand. I held it tight, and saw his expression turn to that of a child in the silent moment before it cries.

November

The final lesson

Morrie died eight days ago.

He went the way he wanted, serenely, while sleeping. His immediate family was in the room, and even though the doctor said “any minute now,” Morrie, unconscious, hung on for a full day, his heart pounding, doing all the work his lungs could not, until his loved ones finally stepped into the kitchen for a few minutes rest.

Then — and I believe this was intentional — he let go, so no one had to watch him die.

The funeral was small, as Morrie and Charlotte wished. The wind blew cold and the skies were grey. His grave site was on a grassy slope above a pond. I thought back to a conversation we’d had last month.

“You know, when I’m gone I hope you’ll come visit me,” he had said.

“Visit you?”

“At my grave. I’ve picked a lovely spot, a good place to sit and ask me questions. I’m not sure how I’ll answer, but I’ll try.”

Still teaching.

Unbelievable.

There’s a poem by W.H. Auden, whom Morrie liked, called “Funeral Blues.” It includes this passage:

He was my North, my South, my East and West

My working week and my Sunday rest

My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song

I thought that love would last forever; I was wrong.

It’s touching, but, as Morrie said, not true. His biggest belief was that love did last forever. It cannot die. This was the lesson he wanted to impart.

How you live will define how you perish, and that all you leave behind is what you gave to others. The thousands of strangers who came to know Morrie Schwartz near the end of his life seem richer for the experience — and those who loved him use his teachings to soothe their grief.

I picture Morrie now, having taken his final course, and I see no disease, no withered body, no wrinkled skin or fragile bones. I see stars and moons and planets, and I see him dancing in the sky.

Morrie Schwartz’s reflections

- Accept the uncertainties, contradictions and tension of opposites in your life.

- Entertain the thought and feeling that the distance between life and death may not be as great as you think.

- Talk openly about your illness with whoever wants to talk with you about it.

- Resist the temptation to think of yourself as useless. It will only lead to depression. Find your own ways of being and feeling useful.

- After you have wept and grieved for your physical losses, cherish the functions and the life you have left.

- Watch for and resist the creeping urge to withdraw from the world.

- Let sadness, grief, despair, depression, bitterness, rage, resentment — all the negative emotions that arise in you — penetrate you. Stay with them as long as you can or until they run their natural course. But do not brood about them. Become reinvolved in life as soon as you can.

- Be grateful that you have been given the time to learn how to die.

- Accept and indulge your passivity and dependency when necessary. But be independent and assertive when you can and need to be.

- If you can’t have large victories or achievements, be grateful and celebrate small ones.

- Find what is divine, holy, or sacred for you. Attend to it, or worship it, in your own way.

- This is the time to do a life review, to make amends, to identify and let go of regrets, to come to terms with unresolved relationships, to tie up loose ends.

- Learn how to live, and you’ll know how to die; learn how to die, and you’ll know how to live.